Introduction

The basic premise of these Educational Articles is this: the decision to not intensively manage the vast majority of public held forest lands for the benefit of the forest, has led us down a curvy road to the present policy of allowing fire (which can be a catastrophic, environmentally degrading force) to “manage” these forests. The litany of fallacies that has been propagated along this road is so great that 100 op-ed pieces would not be sufficient to expose them. These articles are a starting point for exposing the fallacies. We hope that you will take the time to consider the facts presented here, because only an outcry of a majority of citizens will turn us from the destructive path that we are on.

Man as manager

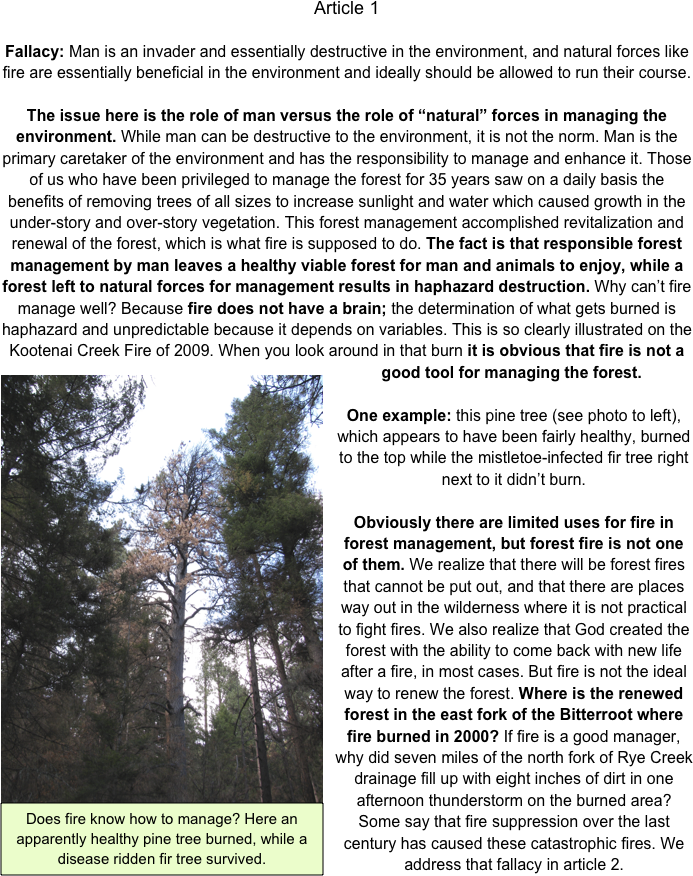

Fire as manager

Article 2

Fallacy: Fire suppression over the last century is one of the main causes of recent catastrophic forest fires.

The false premise is that suppressing fires has led to overstocked forests. In response to this, we offer a different premise to explain the situation. Namely, the lack of intensive forest management over the past thirty years is the main cause of widespread overstocking in the forest. There has been a conscious decision made by public forest managers to set aside large areas of forest for no timber management, under the guise that this would preserve those areas for future generations. Also, in the areas open to forest management, restrictions have been so severe that intensive management has been limited to relatively few acres.

These restrictions suggest that logging somehow harms the forest. The truth is that the benefit that is supposed to come through using fire can be brought about much more effectively using logging and other mechanical means, because it is more easily controlled. With logging, stocking levels are reduced, genetically superior trees are left, and sunlight and water availability increases, stimulating understory growth which provides food for wildlife. When this tool was effectively taken away from forest managers, the result was the unacceptable increase in biomass - more of the forest became overstocked.

Managing the forest under this false premise (meaning we allow forest fires to burn) presents problems (see Article 1 for one of the main problems). Forests are a growing ecosystem; in some places the forest will grow back relatively quickly, recreating overstocking. To solve this issue with fire creates the unacceptable smoke levels which we are experiencing now. When Native Americans used fire in the forest, they probably left the valley after starting it. We do not have the ability or lifestyle to leave the valley while fires burn. Attempting to mimic Native American practices with controlled burns, too often produces unacceptable air quality. Another problem is that fires do a poor job of cleaning up the forest; they leave behind fuel for future fires (see photos below).

It is true that forest fires eliminate overstocking, but the logical conclusion, to which the false premise leads, is a problem. The Lolo National Forest in Montana has 1,981,837 acres, not counting wilderness acres (2008 figures from the USFS). To keep the forest from becoming overstocked, all of that land would need to burn at least once every 75 years. This means that every year 26,424 new acres need to burn (for comparison, the Kootenai Creek Fire was 6,690 acres), and that is just in one national forest. So even if we had allowed more fires to burn, we would still have problems with fires today.

This overstocking in the forest is a problem for firefighters, but it cannot be blamed for the increase in catastrophic forest fires because parts of the forest were overstocked in the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s when there were very few catastrophic fires, and catastrophic fires can burn in well managed forests. What changed, beginning in the late 80’s, that is the real cause of the increase? We will address that in our next article.

© 2011 Greener Forests

This picture is in the Kootenai Creek Fire burn.

In this spot the fire was a ground fire, but you can clearly see that it did not clean up the forest floor.

This picture is also in the Kootenai Creek Fire burn.

Here the fire was a crown fire that burned everything, but all of these trees will fall over and create a messy fuel source for future fires.